It has slowly dawned on me since the start of this dubious ‘age of generative AI’ that multiple experiences, perspectives, and knowledge of the topic within higher education are inevitable. Indeed, these multiplicities can sit within an individual – take me, for example. I am constantly listening to the inner monologue, asking, What’s my position? What’s my position?

I have found myself being the annoying person in the room, trying – mostly failing – to push against getting carried away by hyped-up narratives of ‘embracing’. Meanwhile I see colleagues grappling with what it means for their beloved disciplines and their students’ learning. All the while, I periodically dip into ChatGPT for my own uses.

Reflecting now in January 2025 on the 8 months since our workshop, and the spaces I had imagined we could have opened up during that 90 minutes, I still have that queasy feeling of traversing values and practices that don’t quite fall into alignment. I still don’t know which way is up.

I needed some steady hands – colleagues I trusted and admired to shine an intellectual and values-based light into the murk. With an approaching deadline for the Networked Learning 2024 conference submission, I persuaded Helen Beetham, Rosemarie McIlwhan and Catherine Cronin to help bring a rather ambitious, slightly crazy idea to life for Malta in May 2024. Catherine has written a lovely reflection and details of the workshop itself, capturing it and her own insights beautifully (go read it).

Generating AI Alternatives

The workshop was designed to challenge the beguiling promises of generative AI. It was not going to be efficient, we were aiming to “produce knowledge at a human speed and scale” (Drumm, et al., 2024).

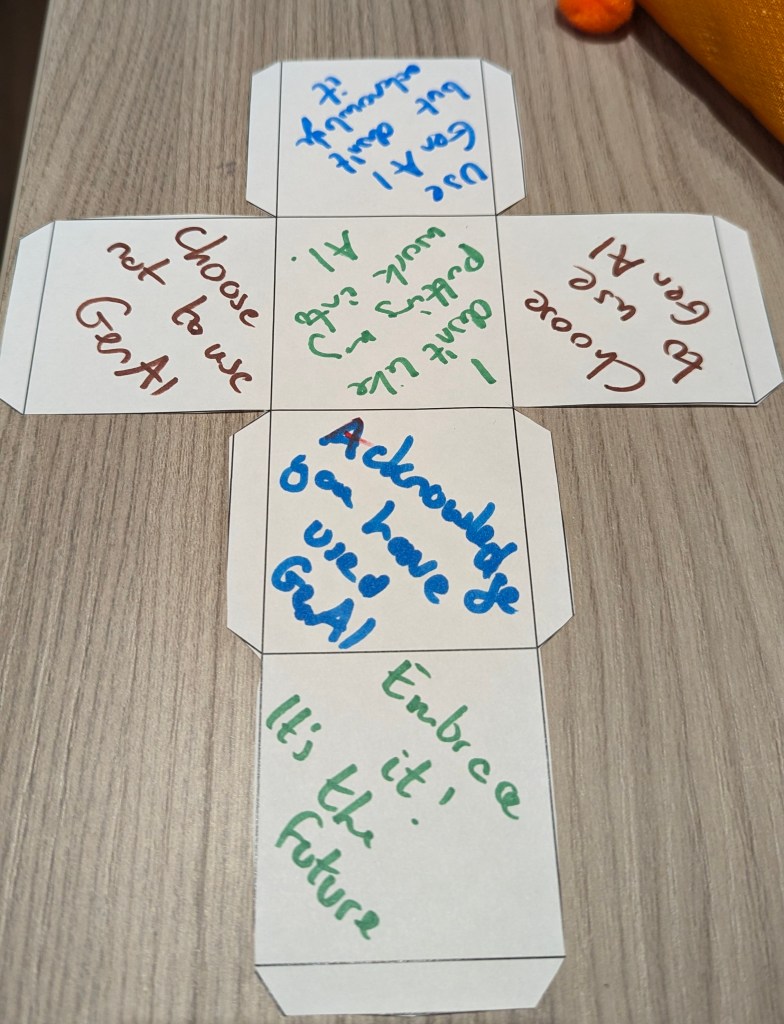

Responding to our provocations (they were not prompts!), participants were asked to draw on rough-tuned thought and instinct – not on scraped datasets or zero shot learning. In just 90 minutes, nearly 100 participants produced a remarkable range of creative responses: on paper, in pen, paint, card, markers, amended printed words, digital texts, poems, anecdotes, drawings, paper sculptures, slides, music, video – some even created with generative AI tools, other in digital media, some analogue.

And in that space between all the structures and spaces of higher education, conferences and the “apparatus” of AI (as Dan MacQuillan aptly calls it in his interview on Helen Beetham’s podcast), we tried to interrupt the relentless business as usual. Like intrusive interstitial ads on a website, we wanted our provocations to get in the way, demand attention and reaction.

The Workshop

The workshop itself is a bit of blur for me. As the only facilitator on site, I was managing the material: the materials, people and reliably unreliable technology, so my attention was split. Still, I remember being blown away by the plenary discussion and the passion, thoughtfulness and generosity of those who spoke and contributed to the text. People spoke of their struggles and that of their colleagues and students. I don’t regret not recording it; it was meant to be a delimited and ephemeral moment – something that can’t be paused and replayed (one reason why I worked in theatre for 10 years). As participants posted their responses on the Padlet, the diversity in thinking, imagination, and heartfelt authenticity was clear. It was a richness I could never (nor any generative AI) have predicted.

There was no homogeneity to the range of artefacts produced during the workshop. No common overriding ideology or singular positionality emerged. Some participants used generative AI tools to create images, others shared positive anecdotes, some critiqued AI capabilities, and others found themes of resistance and sought hope in hopeless contexts.

This for me is the key takeaway. Where generative AI tools converge (what it ‘knows’) of human knowledge into a median point of homogeneity, this workshop provided a counterpoint; a resistance to groupthink and striving for meta themes. Differences could co-exist and had to connect to each other (something I’ve been thinking and writing about a lot in the last year). And again, in opposition to what generative AI would do, there are no binaries or false equivalence of on the one hand and the other; it was unbalanced and slightly messy; it was generating human generation.

What’s Next?

We’re excited to launch a website soon, which will host all the resources and ideas for the workshop, so anyone can take any of these ideas and run with them. Watch out too for further blog posts from my co-conspirators, and more plans to come. If you were one of the participants in the workshop, check your email as we’ll be in touch soon about what’s next.